- Home

- Wilkie Collins

Miss or Mrs Page 8

Miss or Mrs Read online

Page 8

There was silence in the room. They could hear the sound of passing footsteps in the street. He stood perfectly still on the spot where they had struck him dumb by the disclosure, supporting himself with his right hand laid on the head of a sofa near him. The sisters drew back horror-struck into the furthest corner of the room. His face turned them cold. Through the mute misery which it had expressed at first, there appeared, slowly forcing its way to view, a look of deadly vengeance which froze them to the soul. They whispered feverishly one to the other, without knowing what they were talking of, without hearing their own voices. One of them said, “Ring the bell!” Another said, “Offer him something, he will faint.” The third shuddered, and repeated, over and over again, “Why did we do it? Why did we do it?”

He silenced them on the instant by speaking on his side. He came on slowly, by a step at a time, with the big drops of agony falling slowly over his rugged face. He said, in a hoarse whisper, “Write me down the name of the church—there.” He held out his open pocketbook to Amelia while he spoke. She steadied herself, and wrote the address. She tried to say a word to soften him. The word died on her lips. There was a light in his eyes as they looked at her which transfigured his face to something superhuman and devilish. She turned away from him, shuddering.

He put the book back in his pocket, and passed his handkerchief over his face. After a moment of indecision, he suddenly and swiftly stole out of the room, as if he was afraid of their calling somebody in, and stopping him. At the door he turned round for a moment, and said, “You will hear how this ends. I wish you good-morning.”

The door closed on him. Left by themselves, they began to realize it. They thought of the consequences when his back was turned and it was too late.

The Graybrookes! Now he knew it, what would become of the Graybrookes? What wou ld he do when he got back? Even at ordinary times—when he was on his best behavior—he was a rough man. What would happen? Oh, good God! what would happen when he and Natalie next stood face to face? It was a lonely house—Natalie had told them about it—no neighbors near; nobody by to interfere but the weak old father and the maiden aunt. Something ought to be done. Some steps ought to be taken to warn them. Advice—who could give advice? Who was the first person who ought to be told of what had happened? Lady Winwood? No! even at that crisis the sisters still shrank from their stepmother—still hated her with the old hatred! Not a word to her! They owed no duty to her! Who else could they appeal to? To their father? Yes! There was the person to advise them. In the meanwhile, silence toward their stepmother—silence toward every one till their father came back!

They waited and waited. One after another the precious hours, pregnant with the issues of life and death, followed each other on the dial. Lady Winwood returned alone. She had left her husband at the House of Lords. Dinner-time came, and brought with it a note from his lordship. There was a debate at the House. Lady Winwood and his daughters were not to wait dinner for him.

TENTH SCENE.

Green Anchor Lane.

An hour later than the time at which he had been expected, Richard Turlington appeared at his office in the city.

He met beforehand all the inquiries which the marked change in him must otherwise have provoked, by announcing that he was ill. Before he proceeded to business, he asked if anybody was waiting to see him. One of the servants from Muswell Hill was waiting with another parcel for Miss Lavinia, ordered by telegram from the country that morning. Turlington (after ascertaining the servant’s name) received the man in his private room. He there heard, for the first time, that Launcelot Linzie had been lurking in the grounds (exactly as he had supposed) on the day when the lawyer took his instructions for the Settlement and the Will.

In two hours more Turlington’s work was completed. On leaving the office—as soon as he was out of sight of the door—he turned eastward, instead of taking the way that led to his own house in town. Pursuing his course, he entered the labyrinth of streets which led, in that quarter of East London, to the unsavory neighborhood of the river-side.

By this time his mind was made up. The forecast shadow of meditated crime traveled before him already, as he threaded his way among his fellow-men.

He had been to the vestry of St. Columb Major, and had satisfied himself that he was misled by no false report. There was the entry in the Marriage Register. The one unexplained mystery was the mystery of Launce’s conduct in permitting his wife to return to her father’s house. Utterly unable to account for this proceeding, Turlington could only accept facts as they were, and determine to make the most of his time, while the woman who had deceived him was still under his roof. A hideous expression crossed his face as he realized the idea that he had got her (unprotected by her husband) in his house. “When Launcelot Linzie does come to claim her,” he said to himself, “he shall find I have been even with him.” He looked at his watch. Was it possible to save the last train and get back that night? No—the last train had gone. Would she take advantage of his absence to escape? He had little fear of it. She would never have allowed her aunt to send him to Lord Winwood’s house, if she had felt the slightest suspicion of his discovering the truth in that quarter. Returning by the first train the next morning, he might feel sure of getting back in time. Meanwhile he had the hours of the night before him. He could give his mind to the serious question that must be settled before he left London—the question of repaying the forty thousand pounds. There was but one way of getting the money now. Sir Joseph had executed his Will; Sir Joseph’s death would leave his sole executor and trustee (the lawyer had said it!) master of his fortune. Turlington determined to be master of it in four-and-twenty hours—striking the blow, without risk to himself, by means of another hand. In the face of the probabilities, in the face of the facts, he had now firmly persuaded himself that Sir Joseph was privy to the fraud that had been practiced on him. The Marriage-Settlement, the Will, the presence of the family at his country house—all these he believed to be so many stratagems invented to keep him deceived until the last moment. The truth was in those words which he had overheard between Sir Joseph and Launce—and in Launce’s presence (privately encouraged, no doubt) at Muswell Hill. “Her father shall pay me for it doubly: with his purse and with his life.” With that thought in his heart, Richard Turlington wound his way through the streets by the river-side, and stopped at a blind alley called Green Anchor Lane, infamous to this day as the chosen resort of the most abandoned wretches whom London can produce.

The policeman at the corner cautioned him as he turned into the alley. “They won’t hurt me!“ he answered, and walked on to a public-house at the bottom of the lane.

The landlord at the door silently recognized him, and led the way in. They crossed a room filled with sailors of all nations drinking; ascended a staircase at the back of the house, and stopped at the door of the room on the second floor. There the landlord spoke for the first time. “He has outrun his allowance, sir, as usual. You will find him with hardly a rag on his back. I doubt if he will last much longer. He had another fit of the horrors last night, and the doctor thinks badly of him.” With that introduction he opened the door, and Turlington entered the room.

On the miserable bed lay a gray-headed old man of gigantic stature, with nothing on him but a ragged shirt and a pair of patched, filthy trousers. At the side of the bed, with a bottle of gin on the rickety table between them, sat two hideous leering, painted monsters, wearing the dress of women. The smell of opium was in the room, as well as the smell of spirits. At Turlington’s appearance, the old man rose on the bed and welcomed him with greedy eyes and outstretched hand.

“Money, master!” he called out hoarsely. “A crown piece in advance, for the sake of old times!”

Turlington turned to the women without answering, purse in hand.

“His clothes are at the pawnbroker’s, of course. How much?”

“Thirty shillings.”

“Bring them here, and be quick about it. You

will find it worth your while when you come back.”

The women took the pawnbroker’s tickets from the pockets of the man’s trousers and hurried out.

Turlington closed the door, and seated himself by the bedside. He laid his hand familiarly on the giant’s mighty shoulder, looked him full in the face, and said, in a whisper,

“Thomas Wildfang!”

The man started, and drew his huge hairy hand across his eyes, as if in doubt whether he was waking or sleeping. “It’s better than ten years, master, since you called me by my name. If I am Thomas Wildfang, what are you?”

“Your captain, once more.”

Thomas Wildfang sat up on the side of the bed, and spoke his next words cautiously in Turlington’s ear.

“Another man in the way?”

“Yes.”

The giant shook his bald, bestial head dolefully. “Too late. I’m past the job. Look here.”

He held up his hand, and showed it trembling incessantly. “I’m an old man,” he said, and let his hand drop heavily again on the bed beside him.

Turlington looked at the door, and whispered back,

“The man is as old as you are. And the money is worth having.”

“How much?”

“A hundred pounds.”

The eyes of Thomas Wildfang fastened greedily on Turlington’s face. “Let’s hear,” he said. “Softly, captain. Let’s hear.”

When the women came back with the clothes, Turlington had left the room. Their promised reward lay waiting for them on the table, and Thomas Wildfang was eager to dress himself and be gone. They could get but one answer from him to every question they put. He had business in hand, which was not to be delayed. They would see him again in a day or two, with money in his purse. With that assurance he took his cudgel from the corner of the room, and stalked out swiftly by the back door of the house into the night.

ELEVENTH SCENE.

Outside the House

The evening was chilly, but not cold for the time of year. There was no moon. The stars were out, and the wind was quiet. Upon the whole, the inhabitants of the little Somersetshire village of Baxdale agreed that it was as fine a Christmas-eve as they could remember for some years past.

Toward eight in the evening the one small street of the village was empty, except at that part of it which was occupied by the public-house. For the most part, people gathered round their firesides, with an eye to their suppers, and watched the process of cooking comfortably indoors. The old bare, gray church, situated at some little distance from the village, looked a lonelier object than usual in the dim starlight. The vicarage, nestling close under the shadow of the church-tower, threw no illumination of fire-light or candle-light on the dreary scene. The clergyman’s shutters fitted well, and the clergyman’s curtains were closely drawn. The one ray of light that cheered the wintry darkness streamed from the unguarded window of a lonely house, separated from the vicarage by the whole length of the churchyard. A man stood at the window, holding back the shutter, and looking out attentively over the dim void of the burial-ground. The man was Richard Turlington. The room in which he was watching was a room in his own house.

A momentary spark of light flashed up, as from a kindled match, in the burial-ground. Turlington instantly left the empty room in which he had been watching. Passing down the back garden of the house, and crossing a narrow lane at the bottom of it, he opened a gate in a low stone wall beyond, and entered the churchyard. The shadowy figure of a man of great stature, lurking among the graves, advanced to meet him. Midway in the dark and lonely place the two stopped and consulted together in whispers. Turlington spoke first.

“Have you taken up your quarters at the public-house in the village?”

“Yes, master.”

“Did you find your way, while the daylight lasted, to the deserted malt-house behind my orchard wall?”

“Yes, master.”

“Now listen—we have no time to lose. Hide there, behind that monument. Before nine o’clock tonight you will see me cross the churchyard, as far as this place, with the man you are to wait for. He is going to spend an hour with the vicar, at the house yonder. I shall stop short here, and say to him, ‘You can’t miss your way in the dark now—I will go back.’ When I am far enough away from him, I shall blow a call on my whistle. The moment you hear the call, follow the man, and drop him before he gets out of the churchyard. Have you got your cudgel?”

Thomas Wildfang held up his cudgel. Turlington took him by the arm, and felt it suspiciously.

“You have had an attack of the horrors already,” he said. “What does this trembling mean?”

He took a spirit-flask from his pocket as he spoke. Thomas Wildfang snatched it out of his hand, and emptied it at a draught. “All right now, master,” he said. Turlington felt his arm once more. It was steadier already. Wildfang brandished his cudgel, and struck a heavy blow with it on one of the turf mounds near them. “Will that drop him, captain?” he asked.

Turlington went on with his instructions.

“Rob him when you have dropped him. Take his money and his jewelry. I want to have the killing of him attributed to robbery as the motive. Make sure before you leave him that he is dead. Then go to the malt-house. There is no fear of your being seen; all the people will be indoors, keeping Christmas-eve. You will find a change of clothes hidden in the malt-house, and an old caldron full of quicklime. Destroy the clothes you have got on, and dress yourself in the other clothes that you find. Follow the cross-road, and when it brings you into the highroad, turn to the left; a four-mile walk will take you to the town of Harminster. Sleep there tonight, and travel to London by the train in the morning. The next day go to my office, see the head clerk, and say, ‘I have come to sign my receipt.’ Sign it in your own name, and you will receive your hundred pounds. There are your instructions. Do you understand them?”

Wildfang nodded his head in silent token that he understood, and disappeared again among the graves. Turlington went back to the house.

He had advanced midway across the garden, when he was startled by the sound of footsteps in the lane—at that part of it which skirted one of the corners of the house. Hastening forward, he placed himself behind a projection in the wall, so as to see the person pass across the stream of light from the uncovered window of the room that he had left. The stranger was walking rapidly. All Turlington could see as he crossed the field of light was, that his hat was pulled over his eyes, and that he had a thick beard and mustache. Describing the man to the servant on entering the house, he was informed that a stranger with a large beard had been seen about the neighborhood for some days past. The account he had given of himself stated that he was a surveyor, engaged in taking measurements for a new map of that part of the country, shortly to be published.

The guilty mind of Turlington was far from feeling satisfied with the meager description of the stranger thus rendered. He could not be engaged in surveying in the dark. What could he want in the desolate neighborhood of the house and churchyard at that time of night?

The man wanted—what the man found a little lower down the lane, hidden in a dismantled part of the churchyard wall—a letter from a young lady. Read by the light of the pocket-lantern which he carried with him, the letter first congratulated this person on the complete success of his disguise—and then promised that the writer would be ready at her bedroom window for flight the next morning, before the house was astir. The signature was “Natalie,” and the person addressed was “Dearest Launce.”

In the meanwhile, Turlington barred the window shutters of the room, and looked at his watch. It wanted only a quarter to nine o’clock. He took his dog-whistle from the chimney-piece, and turned his steps at once in the direction of the drawing-room, in which his guests were passing the evening.

TWELFTH SCENE.

Inside the House.

The scene in the drawing-room represented the ideal of domestic comfort. The fire of wood and coal mixed burned bri

ghtly; the lamps shed a soft glow of light; the solid shutters and the thick red curtains kept the cold night air on the outer side of two long windows, which opened on the back garden. Snug arm-chairs were placed in every part of the room. In one of them Sir Joseph reclined, fast asleep; in another, Miss Lavinia sat knitting; a third chair, apart from the rest, near a round table in one corner of the room, was occupied by Natalie. Her head was resting on her hand, an unread book lay open on her lap. She looked pale and harassed; anxiety and suspense had worn her down to the shadow of her former self. On entering the room, Turlington purposely closed the door with a bang. Natalie started. Miss Lavinia looked up reproachfully. The object was achieved—Sir Joseph was roused from his sleep.

“If you are going to the vicar’s tonight. Graybrooke,” said Turlington, “it’s time you were off, isn’t it?”

Sir Joseph rubbed his eyes, and looked at the clock on the mantel-piece. “Yes, yes, Richard,” he answered, drowsily, “I suppose I must go. Where is my hat?”

His sister and his daughter both joined in trying to persuade him to send an excuse instead of groping his way to the vicarage in the dark. Sir Joseph hesitated, as usual. He and the vicar had run up a sudden friendship, on the strength of their common enthusiasm for the old-fashioned game of backgammon. Victorious over his opponent on the previous evening at Turlington’s house, Sir Joseph had promised to pass that evening at the vicarage, and give the vicar his revenge. Observing his indecision, Turlington cunningly irritated him by affecting to believe that he was really unwilling to venture out in the dark. “I’ll see you safe across the churchyard,” he said; “and the vicar’s servant will see you safe back.” The tone in which he spoke instantly roused Sir Joseph. “I am not in my second childhood yet, Richard,” he replied, testily. “I can find my way by myself.” He kissed his daughter on the forehead. “No fear, Natalie. I shall be back in time for the mulled claret. No, Richard, I won’t trouble you.” He kissed his hand to his sister and went out into the hall for his hat: Turlington following him with a rough apology, and asking as a favor to be permitted to accompany him part of the way only. The ladies, left behind in the drawing-room, heard the apology accepted by kind-hearted Sir Joseph. The two went out together.

The Woman in White

The Woman in White The Queen of Hearts

The Queen of Hearts Miss Jeromette and the Clergyman

Miss Jeromette and the Clergyman Man and Wife

Man and Wife The Legacy of Cain

The Legacy of Cain Armadale

Armadale The Frozen Deep

The Frozen Deep John Jago's Ghost or the Dead Alive

John Jago's Ghost or the Dead Alive Poor Miss Finch

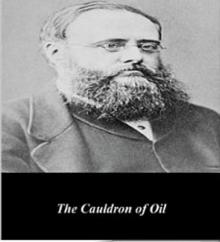

Poor Miss Finch The Cauldron of Oil: A Case Worth Looking At

The Cauldron of Oil: A Case Worth Looking At The Poisoned Meal

The Poisoned Meal The Moonstone

The Moonstone My Lady's Money

My Lady's Money Classic Ghost Stories

Classic Ghost Stories Jezebel's Daughter

Jezebel's Daughter The Devil's Spectacles

The Devil's Spectacles I Say No

I Say No Miss or Mrs.?

Miss or Mrs.? Nine O'Clock

Nine O'Clock The Lawyer's Story of a Stolen Letter

The Lawyer's Story of a Stolen Letter The Two Destinies

The Two Destinies Mr. Percy and the Prophet

Mr. Percy and the Prophet The Law and the Lady

The Law and the Lady The Nun's Story of Gabriel's Marriage

The Nun's Story of Gabriel's Marriage After Dark

After Dark Mr. Captain and the Nymph

Mr. Captain and the Nymph No Name

No Name The Moonstone (Penguin Classics)

The Moonstone (Penguin Classics) Antonina

Antonina Woman in White (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Woman in White (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Miss or Mrs

Miss or Mrs The Dead Alive

The Dead Alive Basil

Basil A Rogue's Life

A Rogue's Life The New Magdalen

The New Magdalen Blind Love

Blind Love Little Novels

Little Novels The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices

The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices The Haunted Hotel

The Haunted Hotel Hide and Seek

Hide and Seek