- Home

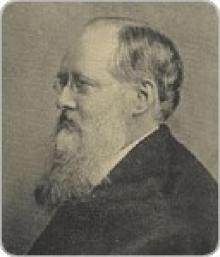

- Wilkie Collins

Basil Page 5

Basil Read online

Page 5

I approached the house. She was at the window—it was thrown wide open. A bird-cage hung rather high up, against the shutter-panel. She was standing opposite to it, making a plaything for the poor captive canary of a piece of sugar, which she rapidly offered and drew back again, now at one bar of the cage, and now at another. The bird hopped and fluttered up and down in his prison after the sugar, chirping as if he enjoyed playing his part of the game with his mistress. How lovely she looked! Her dark hair, drawn back over each cheek so as just to leave the lower part of the ear visible, was gathered up into a thick simple knot behind, without ornament of any sort. She wore a plain white dress fastening round the neck, and descending over the bosom in numberless little wavy plaits. The cage hung just high enough to oblige her to look up to it. She was laughing with all the glee of a child; darting the piece of sugar about incessantly from place to place. Every moment, her head and neck assumed some new and lovely turn—every moment her figure naturally fell into the position which showed its pliant symmetry best. The last-left glow of the evening atmosphere was shining on her—the farewell pause of daylight over the kindred daylight of beauty and youth.

I kept myself concealed behind a pillar of the garden-gate; I looked, hardly daring either to move or breathe; for I feared that if she saw or heard me, she would leave the window. After a lapse of some minutes, the canary touched the sugar with his beak.

"There, Minnie!" she cried laughingly, "you have caught the runaway sugar, and now you shall keep it!"

For a moment more, she stood quietly looking at the cage; then raising herself on tip-toe, pouted her lips caressingly to the bird, and disappeared in the interior of the room.

The sun went down; the twilight shadows fell over the dreary square; the gas lamps were lighted far and near; people who had been out for a breath of fresh air in the fields, came straggling past me by ones and twos, on their way home—and still I lingered near the house, hoping she might come to the window again; but she did not re-appear. At last, a servant brought candles into the room, and drew down the Venetian blinds. Knowing it would be useless to stay longer, I left the square.

I walked homeward joyfully. That second sight of her completed what the first meeting had begun. The impressions left by it made me insensible for the time to all boding reflections, careless of exercising the smallest self-restraint. I gave myself up to the charm that was at work on me. Prudence, duty, memories and prejudices of home, were all absorbed and forgotten in love—love that I encouraged, that I dwelt over in the first reckless luxury of a new sensation.

I entered our house, thinking of nothing but how to see her, how to speak to her, on the morrow; murmuring her name to myself; even while my hand was on the lock of my study door. The instant I was in the room, I involuntarily shuddered and stopped speechless. Clara was there! I was not merely startled; a cold, faint sensation came over me. My first look at my sister made me feel as if I had been detected in a crime.

She was standing at my writing-table, and had just finished stringing together the loose pages of my manuscript, which had hitherto laid disconnectedly in a drawer. There was a grand ball somewhere, to which she was going that night. The dress she wore was of pale blue crape (my father's favourite colour, on her). One white flower was placed in her light brown hair. She stood within the soft steady light of my lamp, looking up towards the door from the leaves she had just tied together. Her slight figure appeared slighter than usual, in the delicate material that now clothed it. Her complexion was at its palest: her face looked almost statue-like in its purity and repose. What a contrast to the other living picture which I had seen at sunset!

The remembrance of the engagement that I had broken came back on me avengingly, as she smiled, and held my manuscript up before me to look at. With that remembrance there returned, too—darker than ever—the ominous doubts which had depressed me but a few hours since. I tried to steady my voice, and felt how I failed in the effort, as I spoke to her:

"Will you forgive me, Clara, for having deprived you of your ride to-day? I am afraid I have but a bad excuse—"

"Then don't make it, Basil; or wait till papa can arrange it for you, in a proper parliamentary way, when he comes back from the House of Commons to-night. See how I have been meddling with your papers; but they were in such confusion I was really afraid some of these leaves might have been lost."

"Neither the leaves nor the writer deserve half the pains you have taken with them; but I am really sorry for breaking our engagement. I met an old college friend—there was business too, in the morning—we dined together—he would take no denial."

"Basil, how pale you look! Are you ill?"

"No; the heat has been a little too much for me—nothing more."

"Has anything happened? I only ask, because if I can be of any use—if you want me to stay at home—"

"Certainly not, love. I wish you all success and pleasure at the ball."

For a moment she did not speak; but fixed her clear, kind eyes on me more gravely and anxiously than usual. Was she searching my heart, and discovering the new love rising, an usurper already, in the place where the love of her had reigned before?

Love! love for a shopkeeper's daughter! That thought came again, as she looked at me! and, strangely mingled with it, a maxim I had often heard my father repeat to Ralph—"Never forget that your station is not yours, to do as you like with. It belongs to us, and belongs to your children. You must keep it for them, as I have kept it for you."

"I thought," resumed Clara, in rather lower tones than before, "that I would just look into your room before I went to the ball, and see that everything was properly arranged for you, in case you had any idea of writing tonight; I had just time to do this while my aunt, who is going with me, was upstairs altering her toilette. But perhaps you don't feel inclined to write?"

"I will try at least."

"Can I do anything more? Would you like my nosegay left in the room?—the flowers smell so fresh! I can easily get another. Look at the roses, my favourite white roses, that always remind me of my own garden at the dear old Park!"

"Thank you, Clara; but I think the nosegay is fitter for your hand than my table."

"Good night, Basil."

"Good night."

She walked to the door, then turned round, and smiled as if she were about to speak again; but checked herself, and merely looked at me for an instant. In that instant, however, the smile left her face, and the grave, anxious expression came again. She went out softly. A few minutes afterwards the roll of the carriage which took her and her companion to the ball, died away heavily on my ear. I was left alone in the house—alone for the night.

VIII.

My manuscript lay before me, set in order by Clara's careful hand. I slowly turned over the leaves one by one; but my eye only fell mechanically on the writing. Yet one day since, and how much ambition, how much hope, how many of my heart's dearest sensations and my mind's highest thoughts dwelt in those poor paper leaves, in those little crabbed marks of pen and ink! Now I could look on them indifferently—almost as a stranger would have looked. The days of calm study, of steady toil of thought, seemed departed for ever. Stirring ideas; store of knowledge patiently heaped up; visions of better sights than this world can show, falling freshly and sunnily over the pages of my first book; all these were past and gone—withered up by the hot breath of the senses—doomed by a paltry fate, whose germ was the accident of an idle day!

I hastily put the manuscript aside. My unexpected interview with Clara had calmed the turbulent sensations of the evening: but the fatal influence of the dark beauty remained with me still. How could I write?

I sat down at the open window. It was at the back of the house, and looked out on a strip of garden—London garden—a close-shut dungeon for nature, where stunted trees and drooping flowers seemed visibly pining for the free air and sunlight of the country, in their sooty atmosphere, amid their prison of high brick walls. But the place gave roo

m for the air to blow in it, and distanced the tumult of the busy streets. The moon was up, shined round tenderly by a little border-work of pale yellow light. Elsewhere, the awful void of night was starless; the dark lustre of space shone without a cloud.

A presentiment arose within me, that in this still and solitary hour would occur my decisive, my final struggle with myself. I felt that my heart's life or death was set on the hazard of the night.

This new love that was in me; this giant sensation of a day's growth, was first love. Hitherto, I had been heart-whole. I had known nothing of the passion, which is the absorbing passion of humanity. No woman had ever before stood between me and my ambitions, my occupations, my amusements. No woman had ever before inspired me with the sensations which I now felt.

In trying to realise my position, there was this one question to consider; was I still strong enough to resist the temptation which accident had thrown in my way? I had this one incentive to resistance: the conviction that, if I succumbed, as far as my family prospects were concerned, I should be a ruined man.

I knew my father's character well: I knew how far his affections and his sympathies might prevail over his prejudices—even over his principles—in some peculiar cases; and this very knowledge convinced me that the consequences of a degrading marriage contracted by his son (degrading in regard to rank), would be terrible: fatal to one, perhaps to both. Every other irregularity—every other offence even—he might sooner or later forgive. This irregularity, this offence, never—never, though his heart broke in the struggle. I was as sure of it, as I was of my own existence at that moment.

I loved her! All that I felt, all that I knew, was summed up in those few words! Deteriorating as my passion was in its effect on the exercise of my mental powers, and on my candour and sense of duty in my intercourse with home, it was a pure feeling towards her. This is truth. If I lay on my death-bed, at the present moment, and knew that, at the Judgment Day, I should be tried by the truth or falsehood of the lines just written, I could say with my last breath: So be it; let them remain.

But what mattered my love for her? However worthy of it she might be, I had misplaced it, because chance—the same chance which might have given her station and family—had placed her in a rank of life far—too far—below mine. As the daughter of a "gentleman," my father's welcome, my father's affection, would have been bestowed on her, when I took her home as my wife. As the daughter of a tradesman, my father's anger, my father's misery, my own ruin perhaps besides, would be the fatal dower that a marriage would confer on her. What made all this difference? A social prejudice. Yes: but a prejudice which had been a principle—nay, more, a religion—in our house, since my birth; and for centuries before it.

(How strange that foresight of love which precipitates the future into the present! Here was I thinking of her as my wife, before, perhaps, she had a suspicion of the passion with which she had inspired me—vexing my heart, wearying my thoughts, before I had even spoken to her, as if the perilous discovery of our marriage were already at hand! I have thought since how unnatural I should have considered this, if I had read it in a book.)

How could I best crush the desire to see her, to speak to her, on the morrow? Should I leave London, leave England, fly from the temptation, no matter where, or at what sacrifice? Or should I take refuge in my books—the calm, changeless old friends of my earliest fireside hours? Had I resolution enough to wear my heart out by hard, serious, slaving study? If I left London on the morrow, could I feel secure, in my own conscience, that I should not return the day after!

While, throughout the hours of the night, I was thus vainly striving to hold calm counsel with myself; the base thought never occurred to me, which might have occurred to some other men, in my position: Why marry the girl, because I love her? Why, with my money, my station, my opportunities, obstinately connect love and marriage as one idea; and make a dilemma and a danger where neither need exist? Had such a thought as this, in the faintest, the most shadowy form, crossed my mind, I should have shrunk from it, have shrunk from my self; with horror. Whatever fresh degradations may be yet in store for me, this one consoling and sanctifying remembrance must still be mine. My love for Margaret Sherwin was worthy to be offered to the purest and perfectest woman that ever God created.

The night advanced—the noises faintly reaching me from the streets, sank and ceased—my lamp flickered and went out—I heard the carriage return with Clara from the ball—the first cold clouds of day rose and hid the waning orb of the moon—the air was cooled with its morning freshness: the earth was purified with its morning dew—and still I sat by my open window, striving with my burning love-thoughts of Margaret; striving to think collectedly and usefully—abandoned to a struggle ever renewing, yet never changing; and always hour after hour, a struggle in vain.

At last I began to think less and less distinctly—a few moments more, and I sank into a restless, feverish slumber. Then began another, and a more perilous ordeal for me—the ordeal of dreams. Thoughts and sensations which had been more and more weakly restrained with each succeeding hour of wakefulness, now rioted within me in perfect liberation from all control.

This is what I dreamed:

I stood on a wide plain. On one side, it was bounded by thick woods, whose dark secret depths looked unfathomable to the eye: on the other, by hills, ever rising higher and higher yet, until they were lost in bright, beautifully white clouds, gleaming in refulgent sunlight. On the side above the woods, the sky was dark and vaporous. It seemed as if some thick exhalation had arisen from beneath the trees, and overspread the clear firmament throughout this portion of the scene.

As I still stood on the plain and looked around, I saw a woman coming towards me from the wood. Her stature was tall; her black hair flowed about her unconfined; her robe was of the dun hue of the vapour and mist which hung above the trees, and fell to her feet in dark thick folds. She came on towards me swiftly and softly, passing over the ground like cloud-shadows over the ripe corn-field or the calm water.

I looked to the other side, towards the hills; and there was another woman descending from their bright summits; and her robe was white, and pure, and glistening. Her face was illumined with a light, like the light of the harvest-moon; and her footsteps, as she descended the hills, left a long track of brightness, that sparkled far behind her, like the track of the stars when the winter night is clear and cold. She came to the place where the hills and the plain were joined together. Then she stopped, and I knew that she was watching me from afar off.

Meanwhile, the woman from the dark wood still approached; never pausing on her path, like the woman from the fair hills. And now I could see her face plainly. Her eyes were lustrous and fascinating, as the eyes of a serpent—large, dark and soft, as the eyes of the wild doe. Her lips were parted with a languid smile; and she drew back the long hair, which lay over her cheeks, her neck, her bosom, while I was gazing on her.

Then, I felt as if a light were shining on me from the other side. I turned to look, and there was the woman from the hills beckoning me away to ascend with her towards the bright clouds above. Her arm, as she held it forth, shone fair, even against the fair hills; and from her outstretched hand came long thin rays of trembling light, which penetrated to where I stood, cooling and calming wherever they touched me.

But the woman from the woods still came nearer and nearer, until I could feel her hot breath on my face. Her eyes looked into mine, and fascinated them, as she held out her arms to embrace me. I touched her hand, and in an instant the touch ran through me like fire, from head to foot. Then, still looking intently on me with her wild bright eyes, she clasped her supple arms round my neck, and drew me a few paces away with her towards the wood.

I felt the rays of light that had touched me from the beckoning hand, depart; and yet once more I looked towards the woman from the hills. She was ascending again towards the bright clouds, and ever and anon she stopped and turned round, wringing her hands and let

ting her head droop, as if in bitter grief. The last time I saw her look towards me, she was near the clouds. She covered her face with her robe, and knelt down where she stood. After this I discerned no more of her. For now the woman from the woods clasped me more closely than before, pressing her warm lips on mine; and it was as if her long hair fell round us both, spreading over my eyes like a veil, to hide from them the fair hill-tops, and the woman who was walking onward to the bright clouds above.

I was drawn along in the arms of the dark woman, with my blood burning and my breath failing me, until we entered the secret recesses that lay amid the unfathomable depths of trees. There, she encircled me in the folds of her dusky robe, and laid her cheek close to mine, and murmured a mysterious music in my ear, amid the midnight silence and darkness of all around us. And I had no thought of returning to the plain again; for I had forgotten the woman from the fair hills, and had given myself up, heart, and soul, and body, to the woman from the dark woods.

Here the dream ended, and I awoke.

It was broad daylight. The sun shone brilliantly, the sky was cloudless. I looked at my watch; it had stopped. Shortly afterwards I heard the hall clock strike six.

My dream was vividly impressed on my memory, especially the latter part of it. Was it a warning of coming events, foreshadowed in the wild visions of sleep? But to what purpose could this dream, or indeed any dream, tend? Why had it remained incomplete, failing to show me the visionary consequences of my visionary actions? What superstition to ask! What a waste of attention to bestow it on such a trifle as a dream!

Still, this trifle had produced one abiding result. I knew it not then; but I know it now. As I looked out on the reviving, re-assuring sunlight, it was easy enough for me to dismiss as ridiculous from my mind, or rather from my conscience, the tendency to see in the two shadowy forms of my dream, the types of two real living beings, whose names almost trembled into utterance on my lips; but I could not also dismiss from my heart the love-images which that dream had set up there for the worship of the senses. Those results of the night still remained within me, growing and strengthening with every minute.

The Woman in White

The Woman in White The Queen of Hearts

The Queen of Hearts Miss Jeromette and the Clergyman

Miss Jeromette and the Clergyman Man and Wife

Man and Wife The Legacy of Cain

The Legacy of Cain Armadale

Armadale The Frozen Deep

The Frozen Deep John Jago's Ghost or the Dead Alive

John Jago's Ghost or the Dead Alive Poor Miss Finch

Poor Miss Finch The Cauldron of Oil: A Case Worth Looking At

The Cauldron of Oil: A Case Worth Looking At The Poisoned Meal

The Poisoned Meal The Moonstone

The Moonstone My Lady's Money

My Lady's Money Classic Ghost Stories

Classic Ghost Stories Jezebel's Daughter

Jezebel's Daughter The Devil's Spectacles

The Devil's Spectacles I Say No

I Say No Miss or Mrs.?

Miss or Mrs.? Nine O'Clock

Nine O'Clock The Lawyer's Story of a Stolen Letter

The Lawyer's Story of a Stolen Letter The Two Destinies

The Two Destinies Mr. Percy and the Prophet

Mr. Percy and the Prophet The Law and the Lady

The Law and the Lady The Nun's Story of Gabriel's Marriage

The Nun's Story of Gabriel's Marriage After Dark

After Dark Mr. Captain and the Nymph

Mr. Captain and the Nymph No Name

No Name The Moonstone (Penguin Classics)

The Moonstone (Penguin Classics) Antonina

Antonina Woman in White (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Woman in White (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Miss or Mrs

Miss or Mrs The Dead Alive

The Dead Alive Basil

Basil A Rogue's Life

A Rogue's Life The New Magdalen

The New Magdalen Blind Love

Blind Love Little Novels

Little Novels The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices

The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices The Haunted Hotel

The Haunted Hotel Hide and Seek

Hide and Seek