- Home

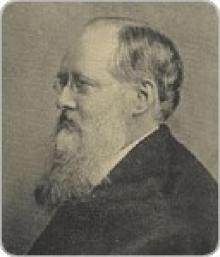

- Wilkie Collins

Man and Wife Page 43

Man and Wife Read online

Page 43

He took her in his arms, and kissed her. At the moment when he

released her Blanche slipped a little note into his hand.

"Read it," she whispered, "when you are alone at the inn."

So they parted on the eve of their wedding day.

CHAPTER THE THIRTY-FIFTH.

THE DAY.

THE promise of the weather-glass was fulfilled. The sun shone on

Blanche's marriage.

At nine in the morning the first of the proceedings of the day

began. It was essentially of a clandestine nature. The bride and

bridegroom evaded the restraints of lawful authority, and

presumed to meet together privately, before they were married, in

the conservatory at Ham Farm.

"You have read my letter, Arnold?"

"I have come here to answer it, Blanche. But why not have told

me? Why write?"

"Because I put off telling you so long; and because I didn't know

how you might take it; and for fifty other reasons. Never mind!

I've made my confession. I haven't a single secret now which is

not your secret too. There's time to say No, Arnold, if you think

I ought to have no room in my heart for any body but you. My

uncle tells me I am obstinate and wrong in refusing to give Anne

up. If you agree with him, say the word, dear, before you make me

your wife."

"Shall I tell you what I said to Sir Patrick last night?"

"About _this?_"

"Yes. The confession (as you call it) which you make in your

pretty note, is the very thing that Sir Patrick spoke to me about

in the dining-room before I went away. He told me your heart was

set on finding Miss Silvester. And he asked me what I meant to do

about it when we were married."

"And you said--?"

Arnold repeated his answer to Sir Patrick, with fervid

embellishments of the original language, suitable to the

emergency. Blanche's delight expressed itself in the form of two

unblushing outrages on propriety, committed in close succession.

She threw her arms round Arnold's neck; and she actually kissed

him three hours before the consent of State and Church sanctioned

her in taking that proceeding. Let us shudder--but let us not

blame her. These are the consequences of free institutions

"Now," said Arnold, "it's my turn to take to pen and ink. I have

a letter to write before we are married as well as you. Only

there's this difference between us--I want you to help me."

"Who are you going to write to?"

"To my lawyer in Edinburgh. There will be no time unless I do it

now. We start for Switzerland this afternoon--don't we?'

"Yes."

"Very well. I want to relieve your mind, my darling before we go.

Wouldn't you like to know--while we are away--that the right

people are on the look-out for Miss Silvester? Sir Patrick has

told me of the last place that she has been traced to--and my

lawyer will set the right people at work. Come and help me to put

it in the proper language, and the whole thing will be in train."

"Oh, Arnold! can I ever love you enough to reward you for this!"

"We shall see, Blanche--in Switzerland."

They audaciously penetrated, arm in arm, into Sir Patrick's own

study--entirely at their disposal, as they well knew, at that

hour of the morning. With Sir Patrick's pens and Sir Patrick's

paper they produced a letter of instructions, deliberately

reopening the investigation which Sir Patrick's superior wisdom

had closed. Neither pains nor money were to be spared by the

lawyer in at once taking measures (beginning at Glasgow) to find

Anne. The report of the result was to be addressed to Arnold,

under cover to Sir Patrick at Ham Farm. By the time the letter

was completed the morning had advanced to ten o'clock. Blanche

left Arnold to array herself in her bridal splendor--after

another outrage on propriety, and more consequences of free

institutions.

The next proceedings were of a public and avowable nature, and

strictly followed the customary precedents on such occasions.

Village nymphs strewed flowers on the path to the church door

(and sent in the bill the same day). Village swains rang the

joy-bells (and got drunk on their money the same evening). There

was the proper and awful pause while the bridegroom was kept

waiting at the church. There was the proper and pitiless staring

of all the female spectators when the bride was led to the altar.

There was the clergyman's preliminary look at the license--which

meant official caution. And there was the clerk's preliminary

look at the bridegroom--which meant official fees. All the women

appeared to be in their natural element; and all the men appeared

to be out of it.

Then the service began--rightly-considered, the most terrible,

surely, of all mortal ceremonies--the service which binds two

human beings, who know next to nothing of each other's natures,

to risk the tremendous experiment of living together till death

parts them--the service which says, in effect if not in words,

Take your leap in the dark: we sanctify, but we don't insure, it!

The ceremony went on, without the slightest obstacle to mar its

effect. There were no unforeseen interruptions. There were no

ominous mistakes.

The last words were spoken, and the book was closed. They signed

their names on the register; the husband was congratulated; the

wife was embraced. They went back aga in to the house, with more

flowers strewn at their feet. The wedding-breakfast was hurried;

the wedding-speeches were curtailed: there was no time to be

wasted, if the young couple were to catch the tidal train.

In an hour more the carriage had whirled them away to the

station, and the guests had given them the farewell cheer from

the steps of the house. Young, happy, fondly attached to each

other, raised securely above all the sordid cares of life, what a

golden future was theirs! Married with the sanction of the Family

and the blessing of the Church--who could suppose that the time

was coming, nevertheless, when the blighting question would fall

on them, in the spring-time of their love: Are you Man and Wife?

CHAPTER THE THIRTY-SIXTH.

THE TRUTH AT LAST.

Two days after the marriage--on Wednesday, the ninth of September

a packet of letters, received at Windygates, was forwarded by

Lady Lundie's steward to Ham Farm.

With one exception, the letters were all addressed either to Sir

Patrick or to his sister-in-law. The one exception was directed

to "Arnold Brinkworth, Esq., care of Lady Lundie, Windygates

House, Perthshire"--and the envelope was specially protected by a

seal.

Noticing that the post-mark was "Glasgow," Sir Patrick (to whom

the letter had been delivered) looked with a certain distrust at

the handwriting on the address. It was not known to him--but it

was obviously the handwriting of a woman. Lady Lundie was sitting

opposite to him at the table. He said, carelessly, "A letter for

Arnold"--and pushed it across to her. Her ladyship

took up the

letter, and dropped it, the instant she looked at the

handwriting, as if it had burned her fingers.

"The Person again!" exclaimed Lady Lundie. "The Person, presuming

to address Arnold Brinkworth, at My house!"

"Miss Silvester?" asked Sir Patrick.

"No," said her ladyship, shutting her teeth with a snap. "The

Person may insult me by addressing a letter to my care. But the

Person's name shall not pollute my lips. Not even in your house,

Sir Patrick. Not even to please _you._"

Sir Patrick was sufficiently answered. After all that had

happened--after her farewell letter to Blanche--here was Miss

Silvester writing to Blanche's husband, of her own accord! It was

unaccountable, to say the least of it. He took the letter back,

and looked at it again. Lady Lundie's steward was a methodical

man. He had indorsed each letter received at Windygates with the

date of its delivery. The letter addressed to Arnold had been

delivered on Monday, the seventh of September--on Arnold's

wedding day.

What did it mean?

It was pure waste of time to inquire. Sir Patrick rose to lock

the letter up in one of the drawers of the writing-table behind

him. Lady Lundie interfered (in the interest of morality).

"Sir Patrick!"

"Yes?"

"Don't you consider it your duty to open that letter?"

"My dear lady! what can you possibly be thinking of?"

The most virtuous of living women had her answer ready on the

spot.

"I am thinking," said Lady Lundie, "of Arnold's moral welfare."

Sir Patrick smiled. On the long list of those respectable

disguises under which we assert our own importance, or gratify

our own love of meddling in our neighbor's affairs, a moral

regard for the welfare of others figures in the foremost place,

and stands deservedly as number one.

"We shall probably hear from Arnold in a day or two," said Sir

Patrick, locking the letter up in the drawer. "He shall have it

as soon as I know where to send it to him."

The next morning brought news of the bride and bridegroom.

They reported themselves to be too supremely happy to care where

they lived, so long as they lived together. Every question but

the question of Love was left in the competent hands of their

courier. This sensible and trust-worthy man had decided that

Paris was not to be thought of as a place of residence by any

sane human being in the month of September. He had arranged that

they were to leave for Baden--on their way to Switzerland--on the

tenth. Letters were accordingly to be addressed to that place,

until further notice. If the courier liked Baden, they would

probably stay there for some time. If the courier took a fancy

for the mountains, they would in that case go on to Switzerland.

In the mean while nothing mattered to Arnold but Blanche--and

nothing mattered to Blanche but Arnold.

Sir Patrick re-directed Anne Silvester's letter to Arnold, at the

Poste Restante, Baden. A second letter, which had arrived that

morning (addressed to Arnold in a legal handwriting, and bearing

the post-mark of Edinburgh), was forwarded in the same way, and

at the same time.

Two days later Ham Farm was deserted by the guests. Lady Lundie

had gone back to Windygates. The rest had separated in their

different directions. Sir Patrick, who also contemplated

returning to Scotland, remained behind for a week--a solitary

prisoner in his own country house. Accumulated arrears of

business, with which it was impossible for his steward to deal

single-handed, obliged him to remain at his estates in Kent for

that time. To a man without a taste for partridge-shooting the

ordeal was a trying one. Sir Patrick got through the day with the

help of his business and his books. In the evening the rector of

a neighboring parish drove over to dinner, and engaged his host

at the noble but obsolete game of Piquet. They arranged to meet

at each other's houses on alternate days. The rector was an

admirable player; and Sir Patrick, though a born Presbyterian,

blessed the Church of England from the bottom of his heart.

Three more days passed. Business at Ham Farm began to draw to an

end. The time for Sir Patrick's journey to Scotland came nearer.

The two partners at Piquet agreed to meet for a final game, on

the next night, at the rector's house. But (let us take comfort

in remembering it) our superiors in Church and State are as

completely at the mercy of circumstances as the humblest and the

poorest of us. That last game of Piquet between the baronet and

the parson was never to be played.

On the afternoon of the fourth day Sir Patrick came in from a

drive, and found a letter from Arnold waiting for him, which had

been delivered by the second post.

Judged by externals only, it was a letter of an unusually

perplexing--possibly also of an unusually interesting--kind.

Arnold was one of the last persons in the world whom any of his

friends would have suspected of being a lengthy correspondent.

Here, nevertheless, was a letter from him, of three times the

customary bulk and weight--and, apparently, of more than common

importance, in the matter of news, besides. At the top the

envelope was marked "_Immediate._." And at one side (also

underlined) was the ominous word, "_Private._."

"Nothing wrong, I hope?" thought Sir Patrick.

He opened the envelope.

Two inclosures fell out on the table. He looked at them for a

moment. They were the two letters which he had forwarded to

Baden. The third letter remaining in his hand and occupying a

double sheet, was from Arnold himself. Sir Patrick read Arnold's

letter first. It was dated "Baden," and it began as follows:

"My Dear Sir Patrick,--Don't be alarmed, if you can possibly help

it. I am in a terrible mess."

Sir Patrick looked up for a moment from the letter. Given a young

man who dates from "Baden," and declares himself to be in "a

terrible mess," as representing the circumstances of the

case--what is the interpretation to be placed on them? Sir

Patrick drew the inevitable conclusion. Arnold had been gambling.

He shook his head, and went on with the letter.

"I must say, dreadful as it is, that I am not to blame--nor she

either, poor thing."

Sir Patrick paused again. "She?" Blanche had apparently been

gambling too? Nothing was wanting to complete the picture but an

announcement in the next sentence, presenting the courier as

carried away, in his turn, by the insatiate passion for play. Sir

Patrick resumed:

"You can not, I am sure, expect _me_ to have known the law. And

as for poor Miss Silvester--"

"Miss Silvester?" What had Miss Silvester to do with it? And what

could be the meaning of the reference to "the law?"

Sir Patrick had re ad the letter, thus far, standing up. A vague

distrust stole over him at the appearance of Miss Silvester's

name in connection with

the lines which had preceded it. He felt

nothing approaching to a clear prevision of what was to come.

Some indescribable influence was at work in him, which shook his

nerves, and made him feel the infirmities of his age (as it

seemed) on a sudden. It went no further than that. He was obliged

to sit down: he was obliged to wait a moment before he went on.

The letter proceeded, in these words:

"And, as for poor Miss Silvester, though she felt, as she reminds

me, some misgivings--still, she never could have foreseen, being

no lawyer either, how it was to end. I hardly know the best way

to break it to you. I can't, and won't, believe it myself. But

even if it should be true, I am quite sure you will find a way

out of it for us. I will stick at nothing, and Miss Silvester (as

you will see by her letter) will stick at nothing either, to set

things right. Of course, I have not said one word to my darling

Blanche, who is quite happy, and suspects nothing. All this, dear

Sir Patrick, is very badly written, I am afraid, but it is meant

to prepare you, and to put the best side on matters at starting.

However, the truth must be told--and shame on the Scotch law is

what _I_ say. This it is, in short: Geoffrey Delamayn is even a

greater scoundrel than you think him; and I bitterly repent (as

things have turned out) having held my tongue that night when you

and I had our private talk at Ham Farm. You will think I am

mixing two things up together. But I am not. Please to keep this

about Geoffrey in your mind, and piece it together with what I

have next to say. The worst is still to come. Miss Silvester's

letter (inclosed) tells me this terrible thing. You must know

that I went to her privately, as Geoffrey's messenger, on the day

of the lawn-party at Windygates. Well--how it could have

happened, Heaven only knows--but there is reason to fear that I

married her, without being aware of it myself, in August last, at

the Craig Fernie inn."

The letter dropped from Sir Patrick's hand. He sank back in the

chair, stunned for the moment, under the shock that had fallen on

him.

He rallied, and rose bewildered to his feet. He took a turn in

the room. He stopped, and summoned his will, and steadied himself

by main force. He picked up the letter, and read the last

sentence again. His face flushed. He was on the point of yielding

himself to a useless out burst of anger against Arnold, when his

better sense checked him at the last moment. "One fool in the

family is, enough," he said. "_My_ business in this dreadful

emergency is to keep my head clear for Blanche's sake."

He waited once more, to make sure of his own composure--and

turned again to the letter, to see what the writer had to say for

himself, in the way of explanation and excuse.

Arnold had plenty to say--with the drawback of not knowing how to

say it. It was hard to decide which quality in his letter was

most marked--the total absence of arrangement, or the total

absence of reserve. Without beginning, middle, or end, he told

the story of his fatal connection with the troubles of Anne

Silvester, from the memorable day when Geoffrey Delamayn sent him

to Craig Fernie, to the equally memorable night when Sir Patrick

had tried vainly to make him open his lips at Ham Farm.

"I own I have behaved like a fool," the letter concluded, "in

keeping Geoffrey Delamayn's secret for him--as things have turned

out. But how could I tell upon him without compromising Miss

Silvester? Read her letter, and you will see what she says, and

how generously she releases me. It's no use saying I am sorry I

wasn't more cautious. The mischief is done. I'll stick at

nothing--as I have said before--to undo it. Only tell me what is

the first step I am to take; and, as long as it don't part me

from Blanche, rely on my taking it. Waiting to hear from you, I

remain, dear Sir Patrick, yours in great perplexity, Arnold

The Woman in White

The Woman in White The Queen of Hearts

The Queen of Hearts Miss Jeromette and the Clergyman

Miss Jeromette and the Clergyman Man and Wife

Man and Wife The Legacy of Cain

The Legacy of Cain Armadale

Armadale The Frozen Deep

The Frozen Deep John Jago's Ghost or the Dead Alive

John Jago's Ghost or the Dead Alive Poor Miss Finch

Poor Miss Finch The Cauldron of Oil: A Case Worth Looking At

The Cauldron of Oil: A Case Worth Looking At The Poisoned Meal

The Poisoned Meal The Moonstone

The Moonstone My Lady's Money

My Lady's Money Classic Ghost Stories

Classic Ghost Stories Jezebel's Daughter

Jezebel's Daughter The Devil's Spectacles

The Devil's Spectacles I Say No

I Say No Miss or Mrs.?

Miss or Mrs.? Nine O'Clock

Nine O'Clock The Lawyer's Story of a Stolen Letter

The Lawyer's Story of a Stolen Letter The Two Destinies

The Two Destinies Mr. Percy and the Prophet

Mr. Percy and the Prophet The Law and the Lady

The Law and the Lady The Nun's Story of Gabriel's Marriage

The Nun's Story of Gabriel's Marriage After Dark

After Dark Mr. Captain and the Nymph

Mr. Captain and the Nymph No Name

No Name The Moonstone (Penguin Classics)

The Moonstone (Penguin Classics) Antonina

Antonina Woman in White (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Woman in White (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Miss or Mrs

Miss or Mrs The Dead Alive

The Dead Alive Basil

Basil A Rogue's Life

A Rogue's Life The New Magdalen

The New Magdalen Blind Love

Blind Love Little Novels

Little Novels The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices

The Lazy Tour of Two Idle Apprentices The Haunted Hotel

The Haunted Hotel Hide and Seek

Hide and Seek